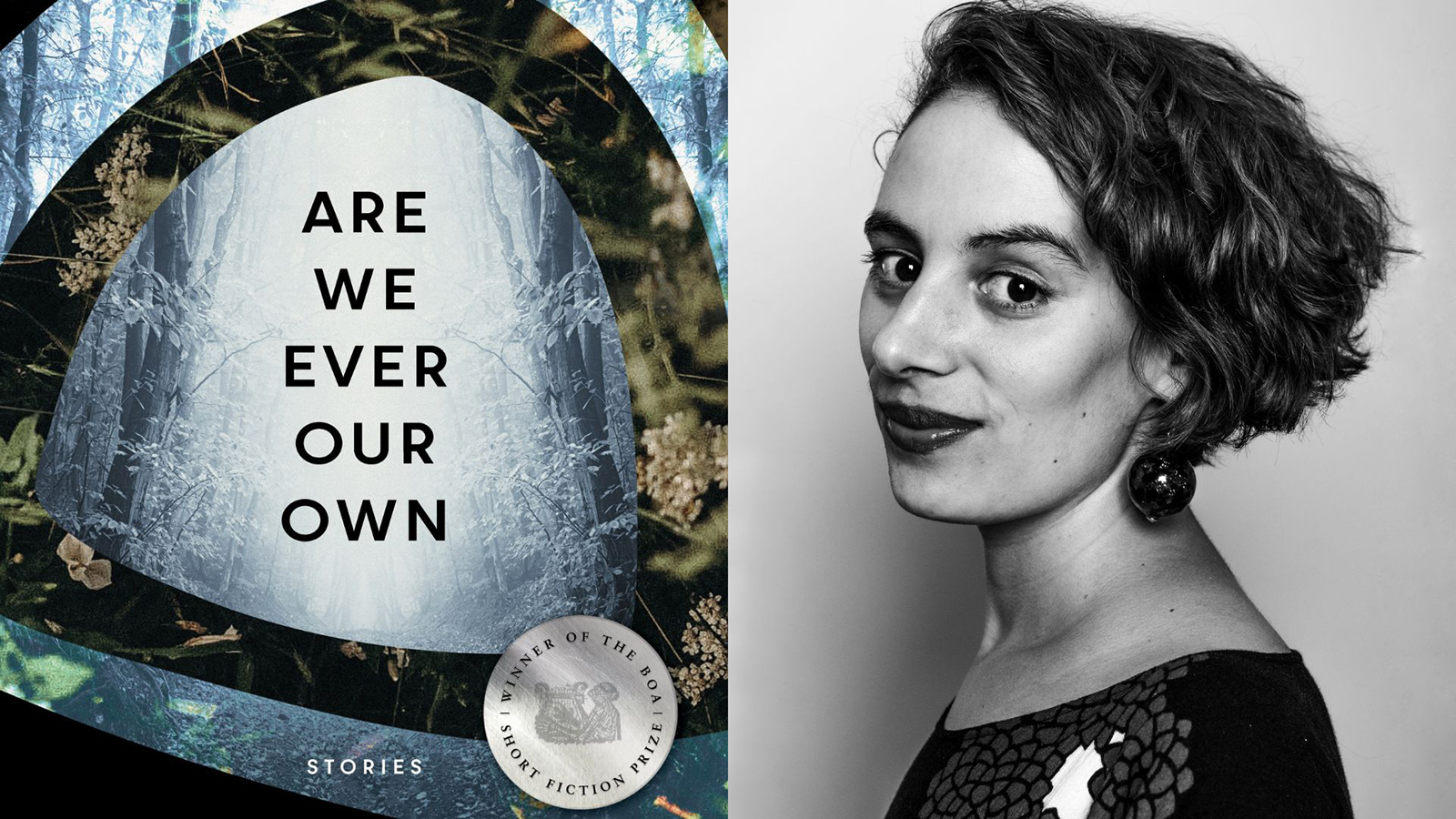

Gabrielle Lucille Fuentes’ Story Collection Unfurls A Family’s Shadows, Myths

June 09, 2022

‘Are We Ever Our Own’ is a multigenerational history of the fictional Armando Castell family told mostly through women narrators.

By Jessica Weiss ’05

Though Gabrielle Lucille Fuentes grew up in Wisconsin, the family stories her parents told often brought her to worlds far away. From Ireland to Cuba, where the family roots extend, the tales were “mystifying and entrancing” and left her hungry to know more about her ancestors.

Fuentes, an assistant professor of English, has now penned a multigenerational history of another diasporic family, the fictional Armando Castells. From Marfa, Texas to La Pieza, Cuba to New York City, the 11 stories that make up the collection, titled “Are We Ever Our Own,” feature immigrants, exiles and artists and almost entirely involve women narrators.

The collection won Fuentes the 10th annual BOA Short Fiction Prize. BOA Publisher Peter Conners said the “richly detailed stories [brim] with magic, hauntings and the multi-generational mythologies we build around our lives.”

This is Fuentes’ first collection of short stories and her second book. In 2017, she published “The Sleeping World,” a novel set in post-Franco Spain about a young woman searching for her lost brother.

At UMD, Fuentes teaches creative writing, fiction workshops and Latinx literature courses for undergraduate and graduate students. We spoke recently to her about her fascination with family stories, why she writes about women and ghosts, her next project and more.

When did your love of stories and storytelling begin?

I was always a big reader and that was the major thing I loved doing as a kid. I did a lot of theater in college and I was planning on being an actor but I fell more in love with writing because I found I could build the world of the story more and I had a lot more agency. So in college I took a bunch of creative writing classes and ended up majoring in it.

Both on my mom’s Irish side and my dad’s Cuban side there’s a lot of storytelling in the tradition, and a rich love of language. I was always very interested in my family’s history and how one’s family shapes them. A lot of the stories in the book are drawing on that history and fictionalizing it.

Did the complex history of U.S. and Cuba relations factor into your upbringing?

Definitely. My mom was raised in Wisconsin, but she was always really interested in Cuban history and would sort of prompt my dad to learn more about it. My dad left when he was really young, right after the revolution, so there was always this kind of push and pull between what he remembered and what the different and competing official stories were. Cuba is this tiny island, but it has an outsized role in American history. To me, Cuba is an amazing way of looking at U.S. history and Latin American history; it’s kind of a microcosm of colonialism, of so much that we experience in the U.S. and throughout the continent.

I understand that one of the book’s stories, “The Night of the Almiqui,” is roughly based on your Cuban grandmother’s life.

A lot of the things my grandmother faced the character “La Abuela” also faces, like anti-Black racism and colorism and also this division between classes and the ways that class and race intersect in Cuba. My grandmother married someone who was white and also of a different class, and her husband’s family was prejudiced against her. Those are stories I grew up hearing. But I also heard the stories of her support of the guerilla fighters—my dad would always tell the story about how on Christmas Eve she brought food up to the rebels up in the mountains. And so I wanted to explore not just the pain that she suffered but her bravery and courage and the sense of agency and freedom she was exercising.

The collection’s stories all focus around women and more specifically, women’s bodies. Is that a theme you’ve always been interested in?

I mainly write about women—the many ways one can be a woman, the ways women are silenced and the ways we push back against that, the different levels of privilege for different women, the physical experience of being a woman. That is central to my writing and always has been. It’s a way for me to write about people who are different from myself but who have a shared experience, so a departure point. And it’s also something that personally and intellectually and emotionally is a central interest to me. It’s my lens for trying to understand the world.

Readers will also find ghosts throughout your work. Can you talk about that?

From both sides of my family, there’s a long tradition of ghosts, not in the sense of spooky ghouls or things that haunt you, but in that you can still experience your loved ones who’ve passed. And a lot of the literature I’ve read and loved explores this. Toni Morrison was a huge influence on me, and she works with ghosts and the ghostly in a lot of her work. Similar to in my family, they’re these sort of travelers or messengers who can impart knowledge, information, or even just a feeling. And I think writing is a type of telling of ghost stories—you move through the past, to the present, and you bring back things that are long gone.

We are in troubled times. How is writing and literature helping you through this moment?

I’m working on a collection of fantasy stories that’s set in a fully imagined world. As Ursula K. Le Guin said, “Fantasy is escapist … If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape?” I think a lot of the fantasy and science fiction being written now is about imagining a different way of living and feeling like the current situation is untenable. I’m not interested in going to Mars. I’m really interested in learning how to live in our world. So for me, the fantasy is not about running away from something but about imagining a new form of existence.

Literature has brought me great pleasure and great joy and also great comfort throughout my entire life. I don’t know where I would be without books. And I also think that literature is able to synthesize and reflect our world and imagine new ones and propel us towards more empathy, more wildness and kindness towards one another.

Fuentes will have a reading at Lost City Books in Washington, D.C., on June 9 and a virtual craft of fiction talk at the Writer's Center on July 28.

Author photo by Ashely Mathieu.